A quick intro for those who have never heard of him...

"Don McCullin (b.1935) has captured photographs of conflict, disaster and devastation in Britain and abroad for over 40 years, including extensive coverage of the Vietnam War and the conflict in Northern Ireland. He’s the recipient of a number of awards, including a CBE in 1993. In 2011, The Imperial War Museum, London, mounted the largest exhibition to date of his work in the UK, Shaped by War: Photographs by Don McCullin. His work is currently on view in War/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath, at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and subsequently touring to LA, Washington and New York."

"Colin Ford, CBE, was the first senior curator of photography at the National Portrait Gallery, 1972-82 and Founding Head of the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television (now the National Media Museum). He was a regular BBC broadcaster for many years, and first interviewed Don McCullin for Radio 4 in 1977. Ford’s Eyewitness: Hungarian Photography in the Twentieth Century (in 2011) was the first photography exhibition ever originated by the Royal Academy."

It was quite an enlightening talk and I discovered many new things about him. After reading his autobiography, borrowed from a friend, it was disappointing to find quite a bit of the information overlapped, I guess it would if you are telling a life story of how you got somewhere and how you started but it did emphasise how some of these talks are just "on a circuit". A bit like when celebs get trotted out for their latest book, or film. I later found a podcast of Colin Ford interviewing him for the National Media Museum, the same questions and the same answers....I know they would be the same answers and I guess there are only so many ways to tell it and it does not take away from the man himself or as Ford described him "the legend" that is Don McCullin.

http://thephotographersgalleryblog.org.uk/2013/01/25/don-mccullin-in-conversation-with-colin-ford/

What made me giggle lots was at the beginning half the information of how the people met etc was wrong...important to get your research right....

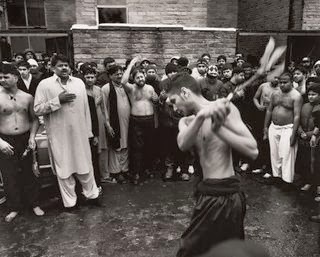

Having said that nonetheless it was very interesting and I jotted down lots of notes which I am now struggling to decipher, I should learn to write properly lol. All his life McCullin seems to have been a risk taker, from hanging around with gangs (first published images were of gangs for the Observer) jaunting off to Berlin with only £42 in his pocket when unable to speak German, to finding himself in the world's worst theatres of war and coming face to face with some of the worlds most dangerous despots. You have to be of a certain personality to handle all of this. He admits he was full of rage and even now will still rant at the world. His upbringing in Finsbury Park gave him a chip on his shoulder and his first photographs were steeped in violence. The gang member photographed eventually killed a policeman and was hung. He feels this rage and feelings of hate have coloured how he takes his images. In a different interview he stated "I grew up in total ignorance, poverty and bigotry, and this has been a burden for me throughout my life, there is still some poison that won't go away, as much as I try to drive it out."

|

| The Guv'nor Finsbury Park London 1958 |

McCullin's period of National Service in the RAF saw him posted to the Canal Zone during the 1956 Suez Crisis, where he worked as a photographer's assistant. He failed to pass the written theory paper necessary to become a photographer in the RAF, and so spent his service in the darkroom. During this period McCullin bought his first camera, a Rolleicord.

McCullin says he felt as a young person he was on a permanent "losers ticket" but he then used his photography and camera to get out of this situation. He took a gamble, defied the Observer and went to Berlin to photograph the soldiers and the building of the Berlin Wall. Some of the results were accidental experimentation as he had the wrong camera for the job so got on the floor and shot from differing angles. Luckily for him and us they came out as well as they did.

|

| Berlin 1961 |

Later on he was prepared to push boundaries even more, friends from Finsbury Park invariably ended up going to prison thinking they had done something daring and risky. His risks took a different direction; the prison he ended up in was in Uganda, after they insisted he pay his hotel bill!

1964 saw McCullin in Cyprus and he received the World Press Photo Award in 1964 for his coverage of this war. In the same year he was awarded the Warsaw Gold Medal.

In fact he is no stranger to awards in 1977, he was made a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society, awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Bradford in 1993 and an honorary degree by the Open University in 1994. He was granted the CBE in 1993, the first photojournalist to receive the honour. The Cornell Capa Award in 2006, The Royal Photographic Society's Special 150th Anniversary Medal and Honorary Fellowship (HonFRPS) in recognition of a sustained, significant contribution to the art of photography in 2003, The Royal Photographic Society's Centenary Medal in 2007 are also claims to fame.

On 4 December 2008, McCullin was conferred with an Honorary Doctorate of Letters by the University of Gloucestershire in recognition of his lifetime's achievement in photojournalism. In 2009 he received the Honorary Fellowship of Hereford College of Arts. In 2011, he was awarded an Honorary Degree (Doctor of Arts) from the University of Bath.

Despite all the recognition he comes across as a modest and compassionate man who appreciates the smallest of gestures. He tells of how in war he still found acts of warmth and humanity, for example being covered by a coat because he decided to stay with the Turkish people capturing the atrocities and telling their story. In the course of this war, his first, he faced the prospect of photographing the dead and the maimed. He felt he had to capture what was there, he had made the decision to go, he knew he was intruding in private moments, he felt shabby and felt although he had conquered something, his fear of death or dead bodies, he also lost something from within. He occasionally questioned why am I here, but "once you take the air ticket there is no turning back. You can't have second decisions" it wasn't done to be cruel or vindictive, its done with compassion and concern, he always looked for permission. Now he thinks if it does not tell a new story or won't change anything he does not photograph it, citing some examples from his recent trip to Syria.

|

| Cyprus conflict 1964 |

One of the questions he was asked after his talk was with regards to if you should help or just photograph and walk away, he replied that even knowing first aid has strings attached, if you go to help someone who is injured, lying in the middle of the road, the chances are you will get hit by the same sniper. The image below below is described as a deposition, like Christ being taken down from the cross, despite not being religious he does see religion in things, "When human beings are suffering, they tend to look up, as if hoping for salvation. And that’s when I press the button." After taking this image he shouted to the men to bring him over, they tripped and fell so he took him on his shoulders and carried him out of the battle.

|

| Vietnam |

|

| Vietnam |

McCullin admitted to being sick of the above image of a shell shocked soldier , he laughed as he told us that he made a mistake and missed it out of the edit for the Sunday Times. Asked if he ever felt if his images had been manipulated to give another meaning or used in a fashion he did not like McCullin replied that he was lucky to have had a lot of control over his images and the captions. He protected them and would supervise the layout and their use despite prompts and suggestions that surely he had other things to do.....we worked for the Sunday Times for about 18 years.

Going to Vietnam and meeting some of the characters there he described as pure Graham Greene, and it was a gigantic war, the battlefield was "help yourself" and nothing now will never be the same; photographers are embedded, they are restricted in their movements. He partially blamed this on the coverage of the Vietnam war, where he spent 4 years, an independent witness of the "mad follies" of war that happened. There is less access now. with more spin to hide realities, western leaders are made more accountable and there is a public outcry over casualty figures. Dictators have no fear of public opinion.

|

| Vietnam |

One of his observations at this time was that war sometimes makes men not act like "real men" but more like "real human beings" which seems a paradox, but men cried, black men cried over white and white men cried over black, segregation and politics didn't matter. But sometimes the soldiers acted inhumanely. The above photograph was taken after American soldiers looted a dead soldier. McCullin thought this wrong, he thought of him as a hero, fighting for his country,with family and paltry possessions. He freely admits to staging this by gathering the scattered belongings together, he wanted to show these pathetic possessions, how the Americans had everything while he had nothing and they had messed about with his body for souvenirs. He thought it disgusting which I found rather telling and a revealed a compassionate side which commentators don't always apply to war photographers. They tend to assume after a while the photographers become immune. McCullin is proof they don't. In another interview on discussing the death of a mother of five from cholera he said "I was looking up to the sky, trying not to let them see that I was crying. I am very emotional, but people don’t know this, I am expected to be the big tough John Wayne of war photography – which I don't want to be."

He likes to be known as a photographer, unhappy with the label that some chose these days of being an artist "I don't want to be called an artist, I don't have the right to practice creativity at the expense of human suffering."

During his talk he brings up Biafra and capturing the plight of the children and young women affected. Again he discussed the ridiculousness (to him) of religion, how these poor women were starving, their children dying and yet he would find graffiti claiming "today I am reborn" etched into the walls. Religion is to blame in many a conflict, Christian Phalange killing the Palestinians, Protestants against Catholics in Northern Ireland...the list is endless.

|

| Biafra |

On photographing both sides in the Northern Ireland conflict he said "photographers don't have enemies, they don't take sides...[paradoxically]... once you see an injustice you do take sides."

|

| Northern Ireland |

|

| West Hartlepool 1963 |

|

| Day Of Ashura, Bradford, 2006 |

"What I would consider my self-portrait, if I had to, would be the Irish tramp who looks like Neptune. Because of his melancholy, his dignity. It is difficult to associate the word “dignity” with conditions such as I photograph, yet dignity is what I try to show."

Don McCullin cites the following photographers who have influenced him: Roger Fenton, Robert Capa, Bill Brandt, Eugene Smith (describing him as bonkers) and William Klein. He greatly admires Chris Killip and believes he has surpassed everyone else in the field of documentary.

He is still learning, about himself, about others, about his environment, carrying around a "war reputation" he describes as a man not changing his clothes. He likes landscapes, still life and other aspects of photography. McCullin likes it when people compliment his landscapes and it makes him feel clean. However he does not like chocolate box landscapes, and being in touch with himself the inner darkness he feels influences how he shoots.He hardly ever sees the "blossom, lights or fluffy clouds." To achieve the deep contrast and richness of his photographs he uses a yellow filter, and when it snows an infra red.

McCullin acknowledges that you can't go to war without some kind of damage, either physical or mental. He welcomed his injuries so he could acknowledge others suffering. Now he wants some time to himself, you go to war you suffer, he has had 55 years of this and now wants time to himself. "I have been manipulated, and I have in turn manipulated others, by recording their response to suffering and misery. So there is guilt in every direction : guilt because I don't practice religion, guilt because I was able to walk away, while this man was dying of starvation or being murdered by another man with a gun. And I am tired of guilt, tired of saying to myself : “I didn’t kill that man on that photograph, I didn’t starve that child.” That’s why I want to photograph landscapes and flowers. I am sentencing myself to peace."

|

| Somerset |

This post, and indeed the talk that I attended in no way can sum up the photographer or his back catalogue. I came away quite pensive, with many questions answered. Some on the ability of a person to willingly go to war, on how can they constantly photograph the horrors that are out there, how does it affect them. Do they walk away unscathed. McCullin confirmed what many before have said, that your background and experiences will affect your photography. That he hasn't walked away unscathed, he is still haunted by things he has seen. Yet despite wanting to walk away he can't, in 2012 he returned to the theatre of war going to Syria and at the time of this talk was planning to return. I hope that whatever has been keeping him safe for so long continues to do so.

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/nov/15/don-mccullin

http://nationalmediamuseumblog.wordpress.com/2013/01/11/don-mccullin-in-conversation-war-photography-still-life/

http://www.horvatland.com/WEB/en/THE80s/PP/ENTRE%20VUES/McCulin/entrevues.htm

No comments:

Post a Comment